I started using an outline for my writing in 9th grade. I couldn't believe how much easier and faster it made writing down my story, especially the first draft. I've been an avid plotter ever since. I find that knowing the big picture helps me to concentrate my creative energy on the little picture. When I know where the story is going, I can concentrate my creativity on details, character growth, and theme.

I've already written about story structure systems and how to use them to teach kids the parts of a story. I mentioned that I picked and chose different elements of different systems to make my own. Today I'd like to go into depth about my system and how it works.

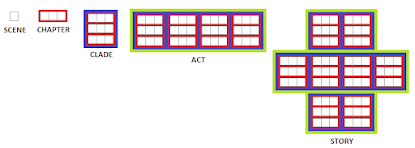

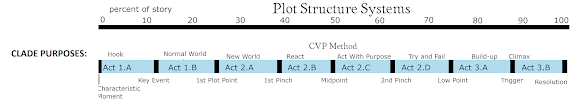

Since all stories are different, and are often different lengths, story structure is plotted out by the percentage of the completed story instead of word count or page number. The main feature of the CVP method (yes, those are my author initials) divides each story into eight roughly equal pieces, which I call clades (more on that later).

Story Metrics:

If I get too metholidcal for you, I apologize. Don't use it if it will stress you out. If quatifying a story this way kills your creativity, feel free to ignore my advice or skip this section. Or, better yet, pick up some bits and pieces that do help you, and set aside the rest.

Using a story structure system breaks down a story into more manigable pieces. It's not unlike how we use other measuring systems, breaking things into smaller pieces until you reach a level that is useful for your current project.

So, if you're familiar with the metric system, if our story was a kilometer: the Acts break it down into hectameters, the clades into dekameters, the chapters into meters, and scenes into decimeters. If you want to get really nerdy, you can have paragraphs into centimeters, sentences into milimeters, and words into micrometers.

The analogy breaks down a little in that I don't usually have a set number of scenes or chapters, just a range (for instance, most DreamRover chapters have 4-6 scenes, and most of my books have an average of three chapters per clade). Clades and Acts do have a set number, eight and three per story, respectively.

Defining Clades:

The three acts can be called the beginning, middle, and end--which is why Act 2, the middle, is twice as long as the others. I split up each act into smaller pieces. Looking at those pieces balances them out and makes the middle feel less daunting.

The eight pieces (Act 1.A, 1.B, 2.A, and so on) are bigger than a scene but smaller than an Act. I'm going to call them clades. A clade in biology is a group of organisms that all evolved from a single common ancestor, like the scenes in these pieces all evolved from the preceding beat (more on those in a minute) and retain common characteristics. Plus, clade sounds cooler than 'piece' or 'section'.

Side note: in Shakespearean times, "Scene" would be the correct word for these pieces. Nowadays a scene means a section of continuous action, usually smaller than a chapter, that is in some way thematically held together.

Beats:

I'm guessing that you've all seen a diagram that looks something like this:

It works for a whole story, but guess what? This framework fits on almost every level of a story too. Each clade, chapter and scene rises up to a climax. This concept is especially important if you're using a publishing platform that pays you per chapter (kindle vella, wattpad, etc).

Pro tip: end most of your chapters just after the climax, but move most of your falling action to the next chapter. It'll entice readers to keep turning pages.

I am defining a beat as the climax of a clade. It's not on the story metric because there is only one in each clade, and the entire clade builds up to it. Beats are the major turning points of the story. Each one has a name and a specific job.

Stories start on a beat. You want an exciting opening that shows your characters and their world, that convinces readers to keep reading. So the first beat has no clade attached. This is why there are nine beats, but only eight clades.

Here are the nine beats. I'll use examples from my books to illustrate each one. I think I've kept things vague enough that nothing will be spoiled, while hopefully leaving enough information to illustrate the point. If you'd rather have stories that you've definitely read or watched before, KM Weiland has a whole database of stories with all of the beats I name here (except the Trigger). I'm describing each beat and clade as a fantasy author, but these will apply for other types of stories (check the database for examples from other genres). For instance, in a romance, the antagonist might be the forces (internal or external) seperating the love interests instead of a villain.

The Nine Beats:

1: The Characteristic moment (the beginning). You want to open with a scene that shows who your character is and how they see the world. In DreamRovers 1, Indra tries to help a sick man in the dreamscape, while Walker tries to help a refugee family. In Mira's Griffin, Mira climbs a cliff and meets a griffin.

2: The Key Event (between Act 1.A and Act 1.B). Something big happens that will make a big difference in your character's life. It's usually something external rather than something that your character chooses for him or herself. In Mira's Griffin, Mira is taken captive by griffins. In Keita's Wings 5, Keita reaches enemy territory and says goodbye to her betrothed.

3. The First Plot Point (between Act 1.B and Act 2.A). The main character(s) actively choose to step into the plot. In The Hero's Journey and The Seven Basic Plot systems, this is called "Accepting the Call". In Mira's Griffin, Mira decides to save a griffin's life instead of escape, which grants her the ability to communicate with them. In The Seventh Clan, Perrin promises to travel with Allee, so that she won't be trapped as a bear, if she will save his father from certain death.

4. The First Pinch Point (between Act 2.A and 2.B). The antagonist rears up his head. The main characters get a major clue about the antagonist and what he or she wants, and face a trial that puts them in danger and reminds them what's at stake. In DreamRovers 1, the antagonist Fenton learns that his neighbors are dreamrovers, people he detests. In Keita's Wings 2, Keita meets a pair of bounty hunters who reveals that someone is offering a huge reward for their capture or death. Notice that in this one, the antagonist is still "off-screen" because his identity is unknown, but the main characters get a hint about his exsistance and motivations.

5. The Midpoint (between Act 2.B and 2.C). Just about every plot structure system includes the midpoint, though the description of its job can vary a bit. The midpoint is a key turning point in the novel where the main character learns the Truth they Need to learn about the world (in KM Weiland's terms). In DreamRovers 1, Indra learns that depending entirely on her beloved dream world can destroy her, and chooses to return to reality. In DreamRovers 2, Walker realizes that clinging to guilt can hurt those around him, and starts to consider forgiving himself for his past.

6. The Second Pinch Point (between Act 2.C and Act 2.D). Again, the antagonist rears his or her head to remind the characters of all they could loose. Keita's Wings 1 has two (I wrote it before studying story structure). In the first, she meets the antagonist in disguise, who tempts her to turn against her companions. In the second, she spies on the antagonist of the series and the antagonist of the book, and has to flee for her life when they find out.

7. The Low Point or Second Plot Point (between Act 2.D and Act 3.A). The main characters thought they had everything figured out, but at this point, everything that could go wrong, does. The antagonists seem to win. The characters feel like they've lost. Often, someone dies. In Mira's Griffin, griffins and humans go to war even though Mira has been working hard to reconcile them. Some people are killed in the battle, and she and her closest companions are captured and mistreated. In Keita's Wings 5, a beloved character is killed, and Keita chooses to wipe out an enemy even though she hates killing.

8. The Trigger (between Act 3.A and 3.B): Something huge happens which kicks off the climax. In DreamRovers 1, the refugees can no longer run away and prepare to stand and face the mob that has been hunting them. In Keita's Wings 1, Keita and her friends set out to rescue their rebel friends who were captured, even though their worst enemies stand in their way.

9. The Resolution (end of Act 3.B): The main characters show that they have grown and changed, and we leave them demonstrating that they are in a better place than in the beginning. If this isn't a series finale, there might still be some loose ends, but the characters still show growth and hope for the future. In Mira's Griffin, the scene closes on her climbing with her close friend/ love interest. She's found her place in her new role as a translator, accepts her interdependance on her companions, and is happy in a place that reconciles her relationships with both people and griffins. In Keita's Wings 6, the scene closes on Keita fully accepting her new home, which she has been trying to find throughout the series.

The Eight Clades:

Important things happen in the spaces between each beat. They may have plenty of action, either physical or emotional. This is especially true if you have multiple chapters inside each clade, because each chapter will still have a climax. The main difference between a chapter climax and a beat is that the beat causes major changes in both your plot and your characters. A chapter climax may be exciting, but it won't have the same power to create change that a beat does. Like Beats, each Clade has its own specific function.

Act 1.A: The Hook

Starts with the Characteristic Moment, ends with the Key Event (in other words, starts by introducing your character and ends with a disruption).

The first clade is all about hooking your reader. Genre plays a huge part here. As Brandon Sanderson explains, you're making promises to your reader about what kind of story they're getting into. Make sure that this first clade represents the kind of story you are writing. The priority here is character and plot first. World-building takes a distant third--you want small quirky tidbits and small details that embody what the setting is. Keep big explinations/info-dumps as small as you can without confusing anyone. There will be a space for world-building, I promise. In Keita's Wings 1, Keita and her new friend escape captivity and struggle to cross a desert without being recaptured. Keita talks a little about the magic system, but mostly shows her abilities as she needs them.

Act 1.B: The Normal World

Starts with the falling action of the Key Event, ends with the First Plot Point (in other words, starts with a reaction to the disruption, and ends with the main character choosing to step into the plot).

This clade is your setup. We see the main character in a world that they are more or less comfortable in. This is where you can slow down and introduce more elements of your world-building. Still not a huge info-dump, but now you've hooked your reader and you can start to give them more depth. In DreamRovers 1, the three point of view characters meet each other and set up a home together.

Act 2.A: The New World

Starts with the falling action of the First Plot Point, ends with the First Pinch Point (in other words, starts with a reaction to their choices, and ends with the influence of the antagonist).

Here's the second part of setting up your world-building, only this time, you're showing us a world that is unfamiliar to your character. It might not be a literal different world. It might not even be a new geographic location, but it's a setting in which your character is not comfortable. In Mira's Griffin, Mira finds herself living among griffin and starts to learn how their society works.

Act 2.B: Reactions

Starts with the falling action of the First Pinch Point, ends with the Midpoint (in other words, starts with a reaction to the antagonist, and ends with a major turning point).

In this section, your characters are going after their wants--which are often in conflict with what they really need. According to KM Weiland, your characters have a Lie they believe about the world. It helped them survive in their Normal World, but now they're getting negative consequences. In Keita's Wings 4, Keita needs to trust her betrothed, but she discovered that the antagonist had been tricking her, and her betrothed had known about it. She still wants to defeat the antagonist, but her attempts to do so without trusting her companions almost result in a deadly shipwreck.

Act 2.C: Act With Purpose

Starts with the falling action of the Midpoint, ends with the Second Pinch Point (in other words, starts with a reaction to a major character change, and ends with a showing from the antagonist).

Armed with new understanding from the midpoint, the main character begins to act instead of be acted upon. In KM Weiland's terms, they still haven't lost their Lie, even though they learned a Truth in the midpoint. This adds to the conflict as they are torn between who they were and who they need to become. In DreamRovers 1, Norma is torn between her new farm (offered to her by her older sister, who plans to turn against her dreamrover family), and the rest of her family.

Act 2.D: Try and Fail

Starts with the falling action of the Second Pinch Point, ends with the Second Plot Point (in other words, starts with a reaction to the influence of the antagonist, a major character change, and ends with a low point).

Your main character actively strikes back against the antagonists. They might even score a victory... only for everything to come crashing down around them. In Mira's Griffin, Mira convinces a griffin to release some of his human slaves and become an ally in their cause to unite their species... but then a battle breaks out.

Act 3.A: Build-up

Starts with the falling action of the Second Plot Point, ends with the Trigger (in other words, starts with a reaction to the low point, and ends with a catapult into the climax).

Save the Cat (specifically Save the Cat Writes a Novel) calls this "The Dark Night of the Soul". The main character reacts to the low point. After a little bit of wallowing, he or she "digs deep" and finds the inner strength to rise again. This is also where subplots get wrapped up. In at least half of the Keita's Wings books (hey, if it ain't broke, don't fix it), Keita finds herself captured and seperated from at least some of her friends, with execution eminent. She must find a clever solution, along with the strength to pull it off, to get free. In book 4, she meets a young boy first and convinces him not to join the battle, wrapping up his subplot.

Act 3.B: Climax

Starts with the trigger, ends with the resolution.

At last, the protagonist faces off directly with the antagonist, and his own inner Lie. Although I don't always use it, Save the Cat Writes a Novel breaks the climax down into five steps, which can be useful if you get stuck or your climax isn't climactical enough. These are 1) Gathering the Team and/or Tools, 2) Enacting the Plan, 3) The Hightower Surprise (the antagonist had a twist up their figurative sleeve), 4) Dig Down Deep, and 5) Execute the New Plan (usually successfully). In DreamRovers 1, the main characters face down the mob trying to exterminate them. They (1) gather their family together and (2) use their cart as a shield while they shoot down their attackers, until (3) enforcements arrive from the other direction. (4) Each main character finds a way to use their strengths. (5) Combined, they escape... but, since this is the first book in the series, they still face exile in the wilderness with limited supplies (okay, that's a minor spoiler, but did you really think I was going to kill off the family in book 1 of a trilogy?)

So, that's the CVP method for story structures. It's mostly adapted from KM Weiland's system, which was expanded mainly from Dan Well's Seven-Point System, which he expanded from a Star Trek roleplaying guide. Don't you love how the internet allows people to build and grow and learn from each other? I'd love it if any of you want to run with these ideas and come up with your own system. If you do, please let me know!